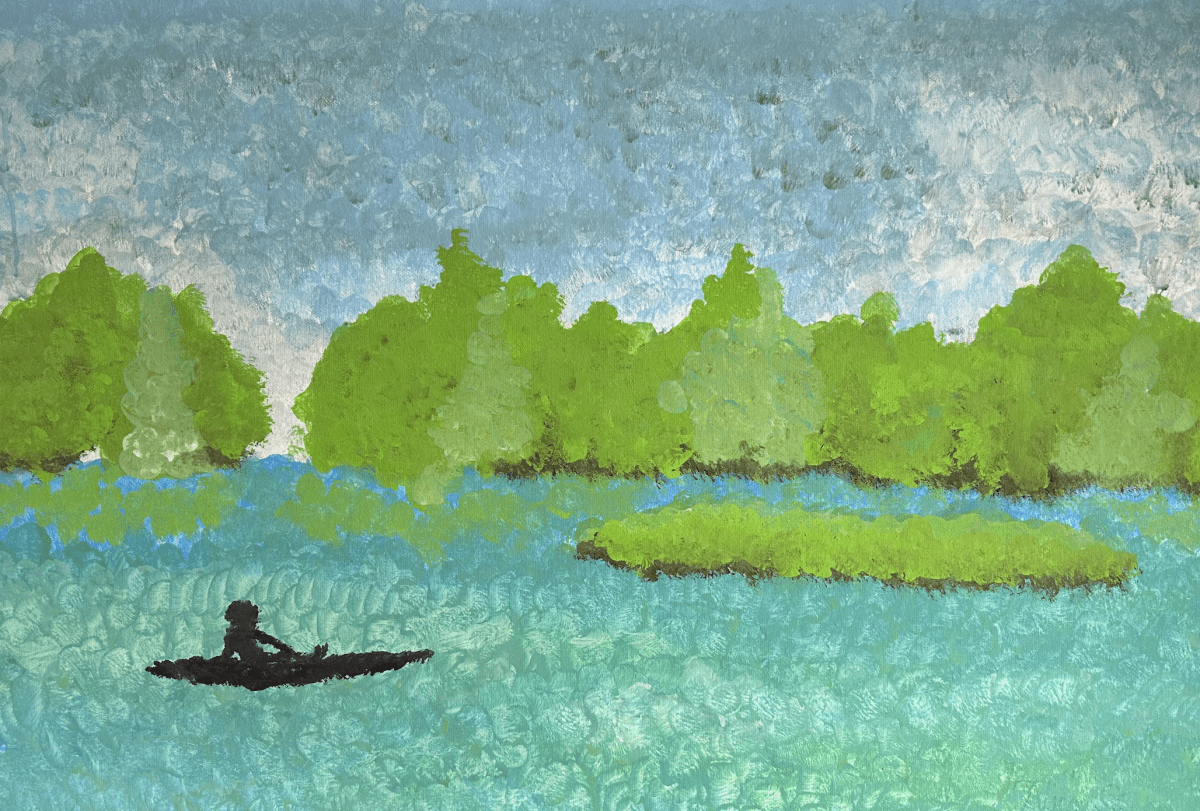

Artwork by: Nico Cordonier-Gehring

By: Nico Cordonier-Gehring, Canada/Germany/Switzerland/UK

Introduction

The cultural, economic, and political history of the Fenlands, including my Cambridgeshire home in East Anglia, offer an inspiring tale of biodiversity ravages, resistance and rewildings. Across nearly 1,500 square miles of southeastern Lincolnshire, most of Cambridgeshire including parts of historic Huntingdonshire, and the westernmost parts of Norfolk and Suffolk, the Fens lie inland of the Wash. I was raised in this region where my grandfather and ancestors made their homes, and it is beautiful with wide open skies, vast misty wetlands, unique and wonderful wildlife, and distinct local communities. Local communities here hold a rich history, interwoven with indigenous religious practices and a spirit of resistance against external forces and exploitation, dating back to the days of the Gyrwas (the Fenlanders, or Fennish commoners) under King Canute. The history of Fenlands peoples and nature is a story of resistance to the destruction of biodiversity lands and livelihoods, which continues to this day through the conservation, carbon sink, and rewilding projects of local communities, youth, historians and scientists, including from the University of Cambridge.

Cultural history of environmental stewardship

The independence and cultural identity of local fenlands Peoples has always been specially connected to the stewardship of the land and waterways. As archaeological and anthropological evidence reveals, the beliefs of the original fenland peoples were marked by a profound respect for nature. A pantheon of spirits and deities were associated with the natural features of their environment. Water, in particular, held sacred significance due to its abundance and vital role in daily lives. The Fenlanders worshipped various water spirits, believed to inhabit the rivers, lakes, and marshes. These spirits were seen as both protectors and potential threats, necessitating rituals to appease them and ensure safe passage and bountiful fishing.

Sacred sites include springs, wells, and groves, and many of these survive to this day, albeit overwritten or repurposed by Christian monasteries or churches. For example, the cathedral and monastery at Ely were built on historic pagan ritual sites. Over time, the imposition of Christianity transformed the religious landscape of the Fenlands. Many local practices were either absorbed into Christian rituals or suppressed, although traces of indigenous beliefs persisted within a Christian framework. For instance, sacred wells became associated with saints, like our Lady of Walsingham or the wells at Walsingham Abbey, and seasonal festivals with processions were adapted into Christian celebrations.

The distinct cultural identity and local knowledge of the Fenland peoples has played a crucial role in resistance against external forces, especially during periods of conquest. The encroachment of Roman, Saxon, and later Norman influences brought attempts to impose new government, laws, practices and administrative controls. However, the fenlanders fought back. Control and invasion was fiercely resisted by the locals, including Hereward the Wake, a local hero who led a rebellion against Norman rule in the 11th Century. His legacy symbolises the enduring spirit of resistance and the defence of local traditions, and inspires local youth, even to this day.

Political history of the Fenlands

The Fenland’s unique ecology and geography, with isolated island homes, floating reeds and shifting lakes and riverbeds, provided areas of retreat from enemies and allowed considerable independence in terms of religion and beliefs. And it is through the draining and destruction of these unique wetlands, threatening the wildlife and rich natural systems with destruction, that very nearly destroyed the Fenlands identity, culture and local livelihoods from the 1600s onwards. For centuries, lords and aristocrats advanced proposals to enclose the commons, then drain the Fens to access the naturally rich soil for farming.

As one historical example, the Isle of Axholme wetlands commons were guaranteed by ancient treaties such as the 1359 Axholme Deed of John de Mowbray, which was kept a locked iron-bound chest in the parish church of Haxey under a stained-glass window of Sir John holding the accord. When Cornelius Vermuyden, a Dutch entrepreneur, sought to violate these rights with a company of ‘Adventurers’ (investors), over two thousand commoners resisted. In 1629, local women verbally distracted drainage workers, while men ambushed them, filling in the ditches, smashing tools, and even constructing mock gallows to loom over the diggers, making clear the consequences of continuing to break the Treaty of Axholme. According to government records of 1629, rather than justice, fen people faced penalties and harsh punishments for making their views heard, and refusing to support their own dispossession, including being beaten and jailed. However, they continued to resist, driving cattle through enclosures.

Economic history of the Fenlands

Although local resistance was fierce, the adventurers and investors finally embarked on large-scale enclosure and drainage of the fens in the 1800s, using foreign workers, windmills and then steam pumps to pull the water away from the majority of the fens, filling in the common wetlands with private holdings and farms. A group of wealthy and powerful investors under the Earl of Bedford near Lincoln came together to canalise the fenlands rivers, undertaking massive earthworks, levelling and installing embankments and relief channels, and dredging operations to drain and privatise the collective wetlands areas. Unfortunately, their ‘Bedford Corporation’ also destroyed the local habitat of wildlife and ecosystems, taking away the natural resources and livelihoods of many local fishing and wildcrafting communities. Employing constables and guards, and hiring labourers from outside the area, they built pumps and small channels to disrupt and eliminate the water so that just the fertile mud was left.

These exploitative projects faced heavy opposition from the local villages and fenlands peoples, who worried about their access to eels, fish, waterfowl and game. Local groups organised to burn down pumping stations and refill ditches overnight, they even hosted cultural events and festivals to disguise attempts to disrupt the dredging operations. The fenlands Peoples resisted on all levels, even taking petitions to the Privy Council and to the King in their defence. While the draining eventually succeeded, and vast farmlands were planted, East Anglia is already facing the results of that folly, as the rivers and canals silt up, and the flooding, with only scattered remnants of peat bogs and washes to absorb the rains, becomes worse every year, drowning villages and towns.

Fenlands today: Taking action for conservation

Still, the history of our fens is not over. Local peoples, joined by nature advocates. In the 2000s, local and national governments are working to re-wild areas of the Fenlands, reclaiming, and restoring them in order to prevent flooding and natural disasters in response to climate change and biodiversity loss. The Wicken Fen Vision 2030 plans to nearly quadruple the protected wetlands as a carbon sink and a local biodiversity haven. At the Great Fen, a vast fenland landscape between Peterborough and Huntingdon, as part of two National Nature Reserves, they are undertaking one of largest restoration projects ever for Europe, as landscapes are being restored and transformed for the benefit of both wildlife and people. With the addition of 120 hectares by rewilding Speechly’s Farm in 2023, completes a massive fenland jigsaw, reversing the harmful effects of those drainages from the 1600s to the 1850s, and creating a continuous corridor of natural wetlands between Woodwalton Fen and Holme.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the story of biodiversity resistance and rewilding in the Fenlands highlights the deep connection between a People and the environment. Our Fenland Peoples’ ability to maintain cultural identity and resist external pressures underscores the powerful role of belief systems in shaping and preserving community cohesion. As we explore the history of the Fenlands, we can all learn a deeper appreciation for the resilience and creativity of these communities, and their continued attempts to find a balance between nature and livelihoods, one that respects and restores the local environment and its unique culture.

Bibliography

Ash, Eric H. The Draining of the Fens: Projectors, Popular Politics, and State Building in Early

Modern England. Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology. Baltimore (Maryland): Johns Hopkins university press, 2017.

Boyce, James. Imperial Mud: The Fight for the Fens. London: Icon, 2020.

Pryor, Francis. The Fens: Discovering England’s Ancient Depths. London: Apollo, 2020.

Sly, Rex. From Punt to Plough: A History of the Fens. Reprinted. Stroud: Sutton Publ, 2003.

Other Resources Used:

JISC Archives Hub (online: www.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk, last accessed 21 June 2024)

The Ouse Washes (online: www.ousewashes.info, last accessed 21 June 2024)

Literary Norfolk (online: www.literarynorfolk.co.uk, last accessed 21 June 2024)

Wicken Fen (online: www.nationaltrust.org.uk, last accessed 21 June 2024)

The Great Fen (online: www.greatfen.org.uk, last accessed 21 June 2024)