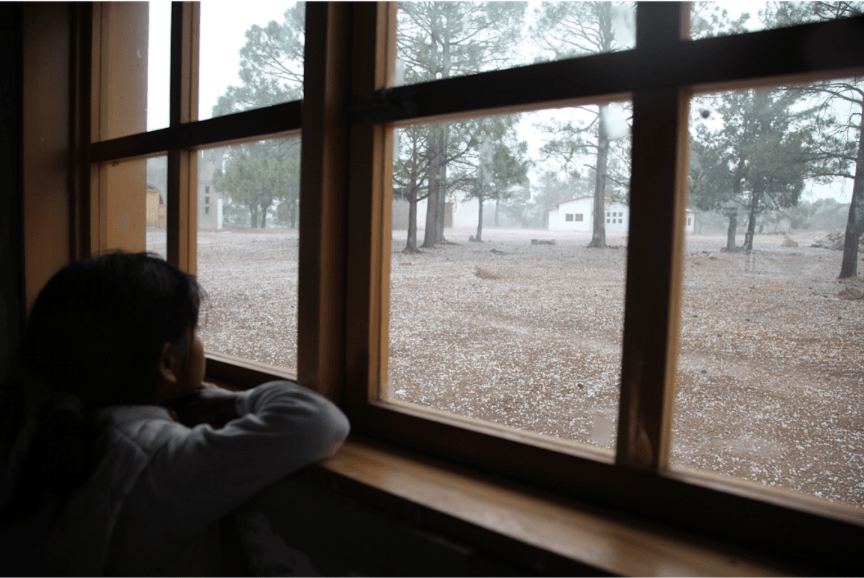

Photograph by Calixtro Vega Valenzuela

By: Emily Viruez Viruez, 18, Bolivia

I feel this sense of loss whenever I think about the woods my mother and I used to go to every weekend; how her free-spirited soul would always be so at ease with the towering trees, endless green. We would walk around those vibrant, living spaces, feeling the energy and beauty fill us. Now, none of those forests exist anymore, or at least, not the way they used to, after having been burnt to ashes by those fires that have recently swept much of our land. What once stood tall, full of life, is now gone. So difficult to fully comprehend that such a thing, so magical in its way, wherein my mom and I would find so much peace, no longer exists, nor shall we again be able to go back to the place. These are not just forests, an ecosystem; these are homes, and their livelihood, memories, and treasures we cannot afford to lose.

The rate at which Bolivian deforestation and the firing of agriculture for expansion take place is in direct conflict with Goal 15 of Sustainable Development, which is aimed at conserving, restoring, and ensuring the sustainable management of our terrestrial ecosystems. The reality is already devastating in a country that houses lots of biodiversity. This means that, up until 2023, a total of 696,000 hectares of forests have been lost, of which the most affected are Santa Cruz and Beni, accounting for a large percentage of 87% (Global Forest Watch, 2023). This situation is even more critical because it is enhanced by destructive practices such as fires, which have destroyed over 4 million hectares so far this year (Fundación Tierra, 2024). Such destruction not only portends a terrible future for Bolivia but also implies a violation of the spirit of SDG 15 by means of land degradation and loss of biodiversity.

Mechanized agriculture, particularly for soybean crop production, contributes to about 30% deforestation in Bolivia (ANAPO, 2021). In the last 15 years, expansion of this crop has been responsible for the destruction of more than one million hectares of forests—which is nearly 60,000 hectares every year (Fundación Tierra, 2024). This huge land clearance is in utter contradiction to SDG 15, which calls for a halt in deforestation and the implementation of methods leading to sustainable use of land. Land use that has been intensive, previously covered by forests, is not only an economic issue but a tragedy to the ecological balance of Bolivia and to its global commitments.

The soy complex is located almost exclusively in the eastern part of the department of Santa Cruz, as 99% of its planted area is distributed across provinces such as Ñuflo de Chávez, Chiquitos, Guarayos, Obispo Santistevan, and Sara (ANAPO, 2021). On the other hand, this geography coincides with those territories that have reported significant losses of tree cover due to fires, an aggravating factor for land degradation and clearly violating SDG 15, which calls for preventing such losses and restoring ecosystems. Between 2001 and 2023, 1.38 million hectares of tree cover were lost in Santa Cruz because of fires (Global Forest Watch, 2023). More precisely, Ñuflo de Chávez has been the region with the highest number of fire alerts—reporting 3,255 in the last weeks (Fundación Tierra, 2024). Chiquitos also stands out with losses totaling 1.37 million hectares. All these are not just numbers; they represent entire destroyed

ecosystems, communities displaced, small producers affected, and an uncertain future for our biodiversity.

The extension of soy crops is devastating our forests, and the current farming-spread and fire-infused farming methods are adding to the fire crisis. Such environmental devastation directly interferes with Bolivia’s ability to meet SDG 15, which is of vital importance in assuring the long-term sustainability of our lands and biodiversity. But we cannot just be speaking in terms of what was lost; we have to act based on it. To that effect, here are some concrete steps we can take as a community and as a country. First, reforestation programs. We have to apply large-scale reforestation programs to recover most of the areas affected, especially in Santa Cruz and Beni. We must work through partnerships with local communities and youth-led environmental groups to foster sustainable forestry practices. Second, transition to sustainable agriculture: Introduce the concept of sustainable agriculture such as agroforestry and crop rotation that would minimize deforestation yet still allow agricultural development. Use government subsidies and international partnerships to incentivize soy farmers toward more eco-friendly practices. Third, fire prevention and control programs: These are stricter regulations in terms of prevention or monitoring of fire-based land clearing. Similarly, the uncontrolled wildfire incidents can be restrained by establishing early response mechanisms among local village communities through the provision of some essential fire-fighting tools. Fourth, youth engagement and education: Engage all the youths throughout Bolivia in the conservation of nature through incorporating environmental education in school curricula, and also through awareness campaigns on the impacts caused by deforestation and land degradation. Empower the next generation to ensure the commitment to change is lasting.

I want this to be an appeal, in fact, to all young people out there in the world: don’t stay silent. What is happening in Bolivia also reflects what happens in many regions of the planet. The time due now is to share the problems so we can solve these challenges together.

References

ANAPO. (2021). Informe Anual de la Asociación Nacional de Productores de Oleaginosas y Trigo.

Fundación Tierra. (2024). Incendios y degradación de la tierra en Bolivia: Un análisis crítico. Fundación Tierra.

Global Forest Watch. (2023). Bolivia Deforestation Rates & Statistics. Global Forest Watch.